On Saturday, May 24th, at approximately 2230h, the HI-SEAS habitat went completely dark. The entire power system suffered a critical failure… due to my own action. The entire story is reminiscent of a mixture of Apollo 13 and Jurassic Park, so Houston, hold on to your butts!

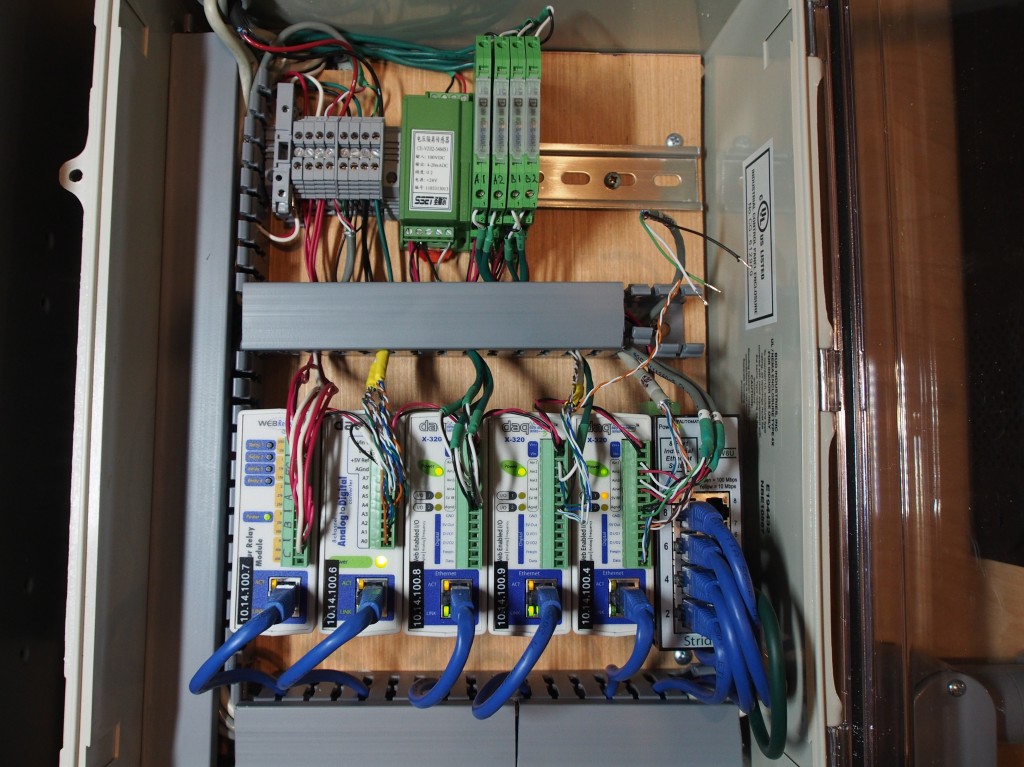

The HI-SEAS habitat is controlled by dozens of web-enabled sensors and relays. The sensors give us the condition of the habitat: the charge of our battery stacks, the output of our AC inverters, the ambient temperature in several locations, the concentration of CO2, and more. The relays switch on fans, the hydronic heating system, and regulate the power generation in response to the sensor array. They’ll even isolate the battery stacks in the event of a power failure to protect the batteries from damage…

I was assigned to a task by one of our Systems Ground Controllers at 1658h: to reset the sensor array connected to our fuel cell backup system. It hadn’t been reporting the condition of the fuel cell for several weeks, and on a recent robotic resupply, our hydrogen source had been replenished, so we needed that data from the fuel cell.

Speaking of sensors, can you reset all of the CBW devices in the container/workshop? Go to the units and pull the terminal block off. Actually if you rock the top back, it will pull out the power pins (24v) and reboot it. — Systems Ground Controller

I received the message as I checked my e-mail prior to bed, around 2200h. It sounded simple enough… “Go to the units and pull the terminal block off.” The instructions couldn’t have been more clear. I hemmed and hawed about whether or not to go ahead and do it that night, or wait until morning.

I should have waited until morning.

The sensor array is located above the battery stacks in the shipping container module, and consists of several rails of electronics: power supplies, fuses, and the sensors themselves. All the sensors are daisy-chained to the same power supply, so pulling the terminal block would disrupt the flow of electricity to all of the sensors. Unfortunately, one of the sensors daisy-chained was controlling a relay that would isolate the battery stacks in the event of a power failure.

I rocked the terminal block off the first sensor. The habitat went dark.

I rocked the terminal block back on. The habitat stayed dark. The only glow came from the battery stacks, which were happily reporting that they were online and in good condition, only they weren’t in discharge mode.

Houston, we have a problem.

The emergency reboot procedure is simple and straight forward. Connect a set of backup batteries to the system by clicking a single fuse on. The backup batteries, in theory, would power on the sensor array, which would then detect that the batteries had been isolated, and close the relay to restore power to the habitat.

Click… Nothing.

The battery backups were dead. The sensor array couldn’t draw power, and the battery stacks weren’t supplying power to the habitat. Cue the backup backup strategy, since the backup battery and the fuel cell couldn’t turn on the sensor array, maybe powering the gasoline generator would.

The gasoline generator has a control box inside the shipping container that allows us to turn on the generator and crank the engine without leaving the habitat.

Click… Crank… Nothing.

The habitat was still completely dark, except for the lights of the battery stacks telling us that they were happily willing to restore power to the entire system, if only they were allowed to talk to the sensor array.

As an exercise in futility, we donned EVA suits and went outside to start the gasoline generator manually. That, finally, succeeded. But it didn’t succeed in powering the sensor array, no. The gasoline generator was running into the same brick wall as the battery stacks, it was ready and willing to supply power, if only the sensor array was turned on.

Time for a backup backup backup plan. The sensor array wasn’t getting power from the backup battery, it wasn’t getting power from the battery stacks or the fuel cells, and it wasn’t getting power from the gasoline generator. Time for a last-ditch effort.

The two MX-C suits have lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries that each supply 12 volts fully charged. The sensor array needs 24 volts to start, and since we have two of the batteries we can connect them in series to get the necessary voltage. Remember, all the while we are doing this, the EVA, the wiring, the testing, the swearing, with nothing more than a couple of flashlights.

Well, it was finally time.

Hold on to your butts. No, not really! It’s a quote from Jurassic Park. — Me

An arc of light jumped as I touched the wires from the MX-C batteries to the terminals of the sensor array. The sensor array clicked, its lights flashed. The habitat stayed dark. For. Five. Breathless. Seconds.

The fans on the battery array were the first indication that something had worked. The started whirring. Next, a series of subsystems flashed to life: the inverter controllers flickered and booted, then the inverters themselves started clicking and whirring. Finally, the habitat lights blinded our dark-adapted eyes. The power was back on.

It took another hour before we had all systems up and running again. Most notably, the generator was still on, and the battery stacks were having a bit of an argument with them over whose job it was to run the habitat power. That kept our communication system offline, but once we shut down the generator, as Ellie Sattler would say, “Mr. Hammond, I think we’re back in business.”

Right before being attacked by a velociraptor. But that’s a story for another day…

(PS, if you look carefully in the featured image, you can see the yellow lasers being fired by the Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea)

i guess this suggests the need for a backup backup backup backup…

Very impressive, Ross and crew. Remember my comment about whether there was any limit to your resourcefulness? See what I mean. God, it must have been nerve wracking when happening but very rewarding when solved. That’s what we were there for.

Well written and a great outside the box thinking.