During the HI-SEAS 2 mission, we tested many implementations of a simulated “delay server”. The delay server was meant to replicate the conditions that a crew on Mars could expect due to the distance, and therefore the speed-of-light delay, from Earth. This caused our e-mail and internet traffic to have a 20-minute one-way delay, and a 40-minute round-trip delay.

For simplicity, one of the early delay server implementations we tested would display a splash page with a 40-minute countdown to simulate the round-trip time that an internet request would take to propagate to Earth and back. Sadly, this meant that we were waiting 40-minutes before we were able to navigate a website.

Obviously, this will not be the method that a Mars mission could expect to use. A Martian base could have a server dedicated to prefetching content from major sites routinely, as well as content a few hyperlinks deep, depending on which crew member was being considered. The experience of browsing the web would be similar to our experience here on Earth, with an odd webpage being unavailable for up to 40-minutes.

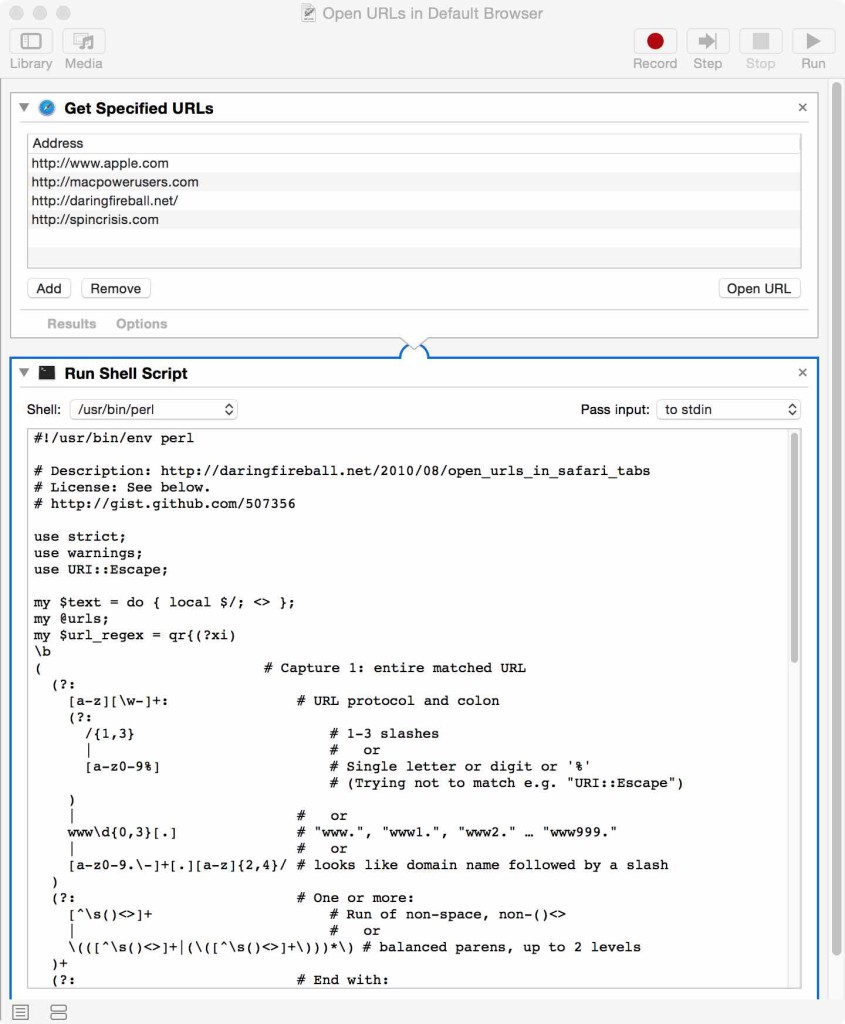

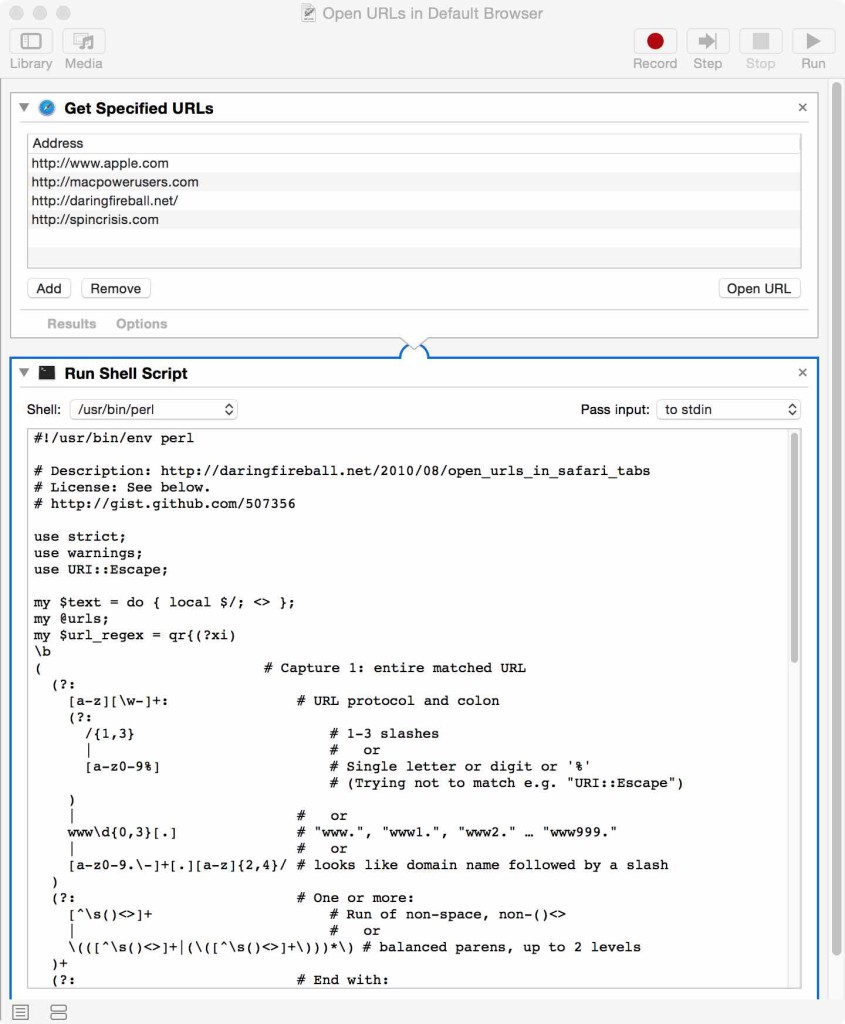

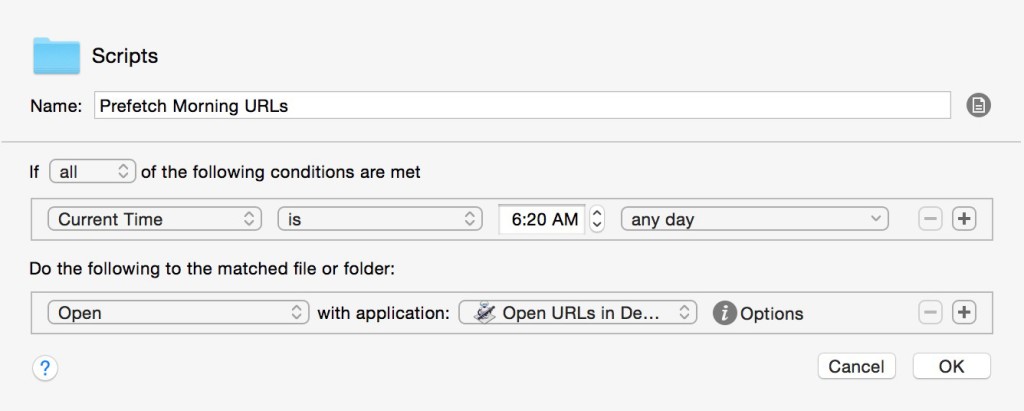

From the HI-SEAS habitat, I was able to simulate this behaviour with a clever Automator script originally written by John Gruber, and modified by Dr. Drang entitled “Open URLs in Default Browser”. By converting the Automator workflow to an application, I could set Hazel to launch Safari (or your default web browser) 40 minutes before my morning alarm, and the webpages I specified would be available when I awoke. If you’d like to download the bundle Automator application that I put together, use this link.

You can modify the URL list by first launching Automator on your Mac, and using the File > Open menu to select it. URLs can be added an removed from the ‘Get Specified URLs’ action. Double check that you save this file as an application, otherwise the Automator window will open every time it is launched.

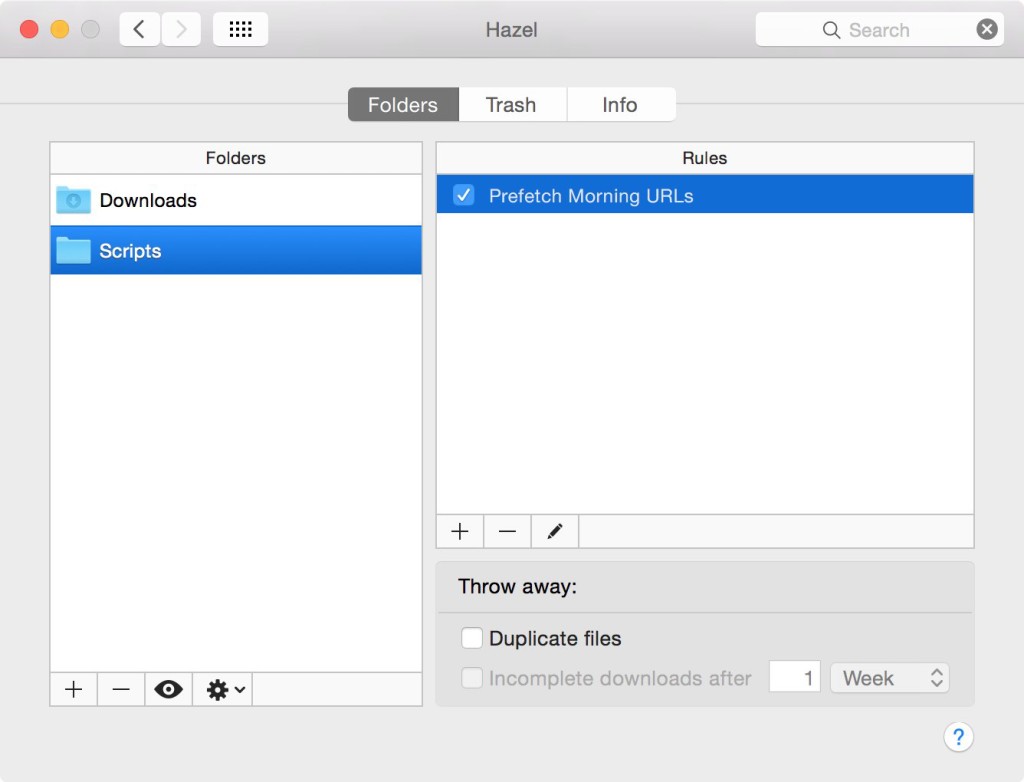

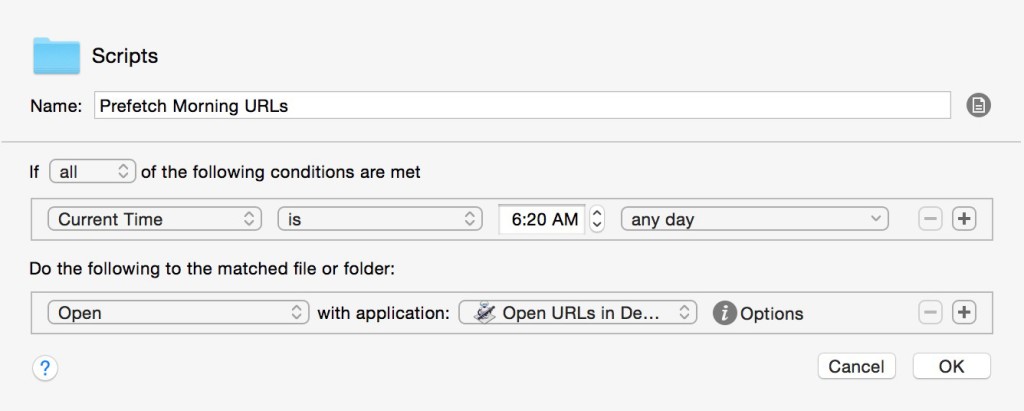

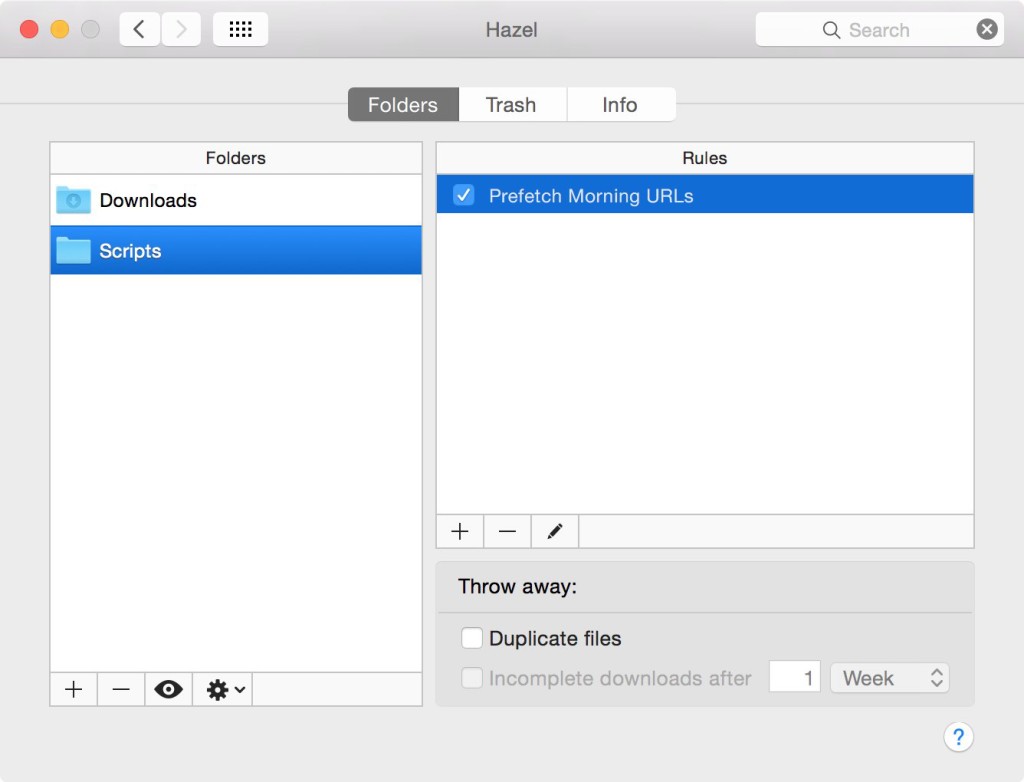

I keep this application, and other scripts in a folder organized into /Documents/Scripts. There, I point Hazel to it, which has a rule called “Prefetch Morning URLs”. The rule only has one condition, namely to check the current time, and then perform an action: Open the Automator application I created. Of course, this means that your computer will have to be on and running for this to work, but you can schedule your computer to wake up using the System Preference > Energy Saver.

If you find yourself routinely opening the same set of tabs, do yourself a favour and spend a few minutes automating the process. Even though I’m no longer on sMars, I continue to use the script so that my morning websites are waiting for me when I get up.